The Null Device

Posts matching tags 'social networks'

2010/7/17

Until now, Google and social software haven't been ideas that went together naturally. The famously engineering-focussed company had experimented with social, though mostly in engineers' 20% time, and with mixed results. Orkut became spectacularly successful in Brazil, but largely bobbed along in the wake of Friendster elsewhere until the vastly technically inferior MySpace came along and seized the market, Google Friend Connect got its lunch eaten by Facebook Connect, and other forays into social made the mistake of being a bit too clever and automatically inferring the user's social graph from their online activity, crossing the line between nifty and disturbing.

Now, however, this is likely to change. There are rumours afoot that Google have made social software a strategic priority, establishing teams to work on the problem of social as part of their regular 80% job, and that a social platform, possibly named Google Me, is in the works. Of course, as far as social platforms go, Facebook have the area sewn up, with a pretty sophisticated API, leaving little space for newcomers (or even Google) to expand into, unless they find and solve problems in the way Facebook does it.

Which brings us to this slide presentation from Google user-experience researcher Paul Adams. The presentation rigorously examines the social uses of software, and the natures of social connections (Adams mentions strong ties and weak ties, and adds a third category, temporary ties, or pairs of people involved in once-off interactions; think someone you buy something from on eBay) and pinpoints possible shortcomings of simple models such as Facebook's (the fact that people have different social circles and needs to expose different facets of their identities to different circles, and that tools such as Facebook's privacy filters have a high overhead to use satisfactorily in this way), not to mention unresolved mismatches between the way human beings intuitively perceive social interaction working and the way it does in the age of social software (for example, we are not intuitively prepared for the idea of our conversations being recorded and made searchable). All in all, it looks like a pretty rigorous survey of social software, condensed down to 216 slides. (An expanded version may be the contents of a book, Social Circles, which comes out in August.)

If Google, who have not given much weight to social software in the past, are investing in this level of research into it, they may well have a Facebook-beating social platform in the works. Though (assuming that it exists, of course) only time will tell whether Google have finally grasped social enough to pull it off.

2010/2/9

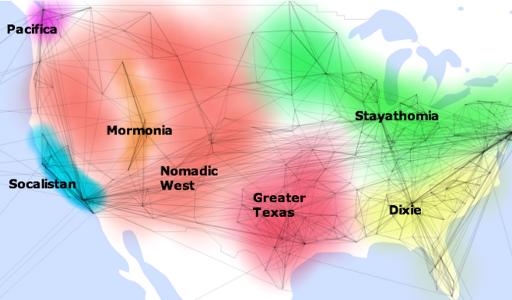

Pete Warden, a programmer and amateur researcher, has analysed the data from public Facebook profiles, including the relative locations of pairs of friends and people's names and fan pages, and used this to divide the US into seven relatively self-contained clusters, which he terms "Stayathomia" (i.e., the northeast to midwest), "Dixie" (the old South), "Greater Texas" (encompassing Oklahoma and Arkansas), "Mormonia" (no prizes for guessing where that is), the "Nomadic West" (places like Idaho, Oregon and Arizona, where people's connections span wide areas), Socalistan (i.e., most of California and parts of Nevada) and Pacifica (essentially Seattle). The clusters were derived from performing cluster analysis on the social graph, and not imposed on the data a priori.

Warden posts various findings he gained from crunching the data on these clusters:

Probably the least surprising of the groupings, the Old South is known for its strong and shared culture, and the pattern of ties I see backs that up. Like Stayathomia, Dixie towns tend to have links mostly to other nearby cities rather than spanning the country. Atlanta is definitely the hub of the network, showing up in the top 5 list of almost every town in the region. Southern Florida is an exception to the cluster, with a lot of connections to the East Coast, presumably sun-seeking refugees. God is almost always in the top spot on the fan pages, and for some reason Ashley shows up as a popular name here, but almost nowhere else in the country.

(Greater Texas:)God shows up, but always comes in below the Dallas Cowboys for Texas proper, and other local sports teams outside the state. I've noticed a few interesting name hotspots, like Alexandria, LA boasting Ahmed and Mohamed as #2 and #3 on their top 10 names, and Laredo with Juan, Jose, Carlos and Luis as its four most popular.

(Mormonia:) It won't be any surprise to see that LDS-related pages like Thomas S. Monson, Gordon B. Hinckley and The Book of Mormon are at the top of the charts. I didn't expect to see Twilight showing up quite so much though, I have no idea what to make of that!Mormons like their vampires sparkly and pro-abstinence; who would have guessed?

(Socalistan:) Keeping up with the stereotypes, God hardly makes an appearance on the fan pages, but sports aren't that popular either. Michael Jackson is a particular favorite, and San Francisco puts Barack Obama in the top spot.Warden also has this tool for browsing aggregate profiles of countries based on their residents' public Facebook profiles.

2008/11/26

New York Magazine has an interesting piece on cities, living alone and the myth of endemic urban loneliness and alienation:

Of all 3,141 counties in the United States, New York County is the unrivaled leader in single-individual households, at 50.6 percent. More than three-quarters of the people in them are below the age of 65. Fifty-seven percent are female. In Brooklyn, the overall number is considerably lower, at 29.5 percent, and Queens is 26.1. But on the whole, in New York City, one in three homes contains a single dweller, just one lone man or woman who flips on the coffeemaker in the morning and switches off the lights at night.

These numbers should tell an unambiguous story. They should confirm the common belief about our city, which is that New York is an isolating, coldhearted sort of place. Mark Twain called it “a splendid desert—a domed and steepled solitude, where the stranger is lonely in the midst of a million of his race.” (This from a man who settled in Hartford, Connecticut.) In J. D. Salinger’s 1952 short story “De Daumier-Smith’s Blue Period,” the main character observes that wishing to be alone “is the one New York prayer that rarely gets lost or delayed in channels, and in no time at all, everything I touched turned to solid loneliness.” Modern movies and art are filled with lonesome New York characters, some so familiar they’ve become their own shorthand: Travis Bickle (in Taxi Driver, calling himself “God’s lonely man”); the forlorn patrons in Nighthawks (inspired, Edward Hopper said, “by a restaurant on New York’s Greenwich Avenue”); Ratso Rizzo (“I gotta get outta here, gotta get outta here,” he kept muttering in Midnight Cowboy … and died before he could).There are several assumptions here: the equation of living alone (outside of a stable nuclear family) with loneliness and psychological toll is one of them. Another one is the great American myth about small-town values, one we see trotted out (often by people on the right of culture-war politics) time and time again.

In American lore, the small town is the archetypal community, a state of grace from which city dwellers have fallen (thus capitulating to all sorts of political ills like, say, socialism). Even among die-hard New Yorkers, those who could hardly imagine a life anywhere else, you’ll find people who secretly harbor nostalgia for the small village they’ve never known.One problem with "small-town values" is that the word is often a dog whistle for a certain brand of reactionary intolerance; a strong in-group-vs.-out-group distinction, knee-jerk traditionalism, bigotry and petty authoritarianism, only painted in folksy Thomas Kincaid colours. One example of this that came around not so long ago was failed US vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin approvingly quoting a fascist newspaper columnist's praise of "small-town America". If small towns stand as a symbol of intolerance and conformism, all things urban could be said to represent the opposite, cosmopolitanism and liberalism.

Cities, in other words, are the ultimate expression of our humanity, the ultimate habitat in which to be ourselves (which may explain why half the planet’s population currently lives in them). And in their present American incarnations—safe, family-friendly, pulsing with life on the street—they’re working at their optimum peak. In Cacioppo’s data, today’s city dwellers consistently rate as less lonely than their country cousins. “There’s a new sense of community in cities, an increase in social capital, an increase in trust,” he says. “It all leads to less alienation.”

Cacioppo and Patrick cite a range of studies showing that students in classes with the best rapport imitate each other’s body language; same goes for athletes on winning teams. The presence of other human beings puts a natural limit on how freakily we can behave. And where better to find them than in cities, where we have more ties? (Think about the sociopathic kids who shot other kids in Red Lake, Minnesota; at Northern Illinois University; at Virginia Tech—what do they have in common? They were living in isolated places.) Robert Sampson, paraphrasing Durkheim, puts it this way: “The tie itself provides health benefits. That’s where I started with my work on crime.”

In any case, recent research has revealed that the equation of living alone and loneliness does not follow; for one, what sociologists call "weak ties" are at least as important to psychological wellbeing as more intimate connections, and cities full of singletons are swarming with potential weak ties (and often stronger ones as well):

“In our data,” adds Lisa Berkman, the Harvard epidemiologist who discovered the importance of social networks to heart patients, “friends substitute perfectly well for family.” This finding is important. It may be true that marriage prolongs life. But so, in Berkman’s view, does friendship—and considering how important friendship is to New Yorkers (home of Friends, after all), where so many of us live on our own, this finding is blissfully reassuring. In fact, Berkman has consistently found that living alone poses no health risk, whether she’s looking at 20,000 gas and electricity workers in France or a random sample of almost 7,000 men and women in Alameda, California, so long as her subjects have intimate ties of some kind as well as a variety of weaker ones. Those who are married but don’t have any civic ties or close friends or relatives, for instance, face greater health risks than those who live alone but have lots of friends and regularly volunteer at the local soup kitchen. “Any one connection doesn’t really protect you,” she says. “You need relationships that provide love and intimacy and you need relationships that help you feel like you’re participating in society in some way.”

In fact, many Internet and city behaviors we consider antisocial have social consequences. Think of people who lug their laptops into public settings. In 2004, Hampton and his colleagues looked at just those people—at Starbucks, in fact, in Seattle and Boston—and concluded that a full third of them were basically using their laptops and interacting at the same time. (Cafés, in other words, were like dog runs, and laptops were like pugs, encouraging interaction among solitaries.) Hampton did a similar study of laptop users in Bryant Park, and the same proportion, or one-third, reported meeting someone they hadn’t before. Fifteen percent of them kept in touch with that person over time (meaning that about 5 percent made lasting ties out of a trip to Bryant Park with a laptop).

Conversely, married people—women especially—have smaller friendship-based social networks than they did as single people, according to Claude Fischer. In a recent phone conversation with the sociologist, I mentioned a related curiosity I came across in a paper about the elderly and social isolation in New York City: The neighborhoods where people were at the greatest risk, it seemed, were in neighborhoods where people seemed very married—family neighborhoods, in fact, like Borough Park and Ridgewood. “That’s not strange at all,” he says. “They’re the prime category of people to be isolated.” He explains that these people “aged in place,” as sociologists like to say, staying in the homes where they raised their own families. Then their spouses died, and so did their cohort (or it moved to a retirement community), and they’re suddenly surrounded by strange families, often of different classes or ethnic backgrounds, with whom they’re likely to have far less in common. “Unless they have children living nearby,” he says, “they’re likely to be quite isolated.”The article concludes with the notion that the internet—another thing often pooh-poohed as alienating and antisocial—functions, in terms of facilitating weak ties, much like a city; in fact, like the ultimate city:

Think about it: Serendipitous encounters between people who know each other well, sort of well, and not at all. People of every type, and with every type of agenda, trying to meet up with others who share that same agenda. An environment that’s alive at all hours, populated by all types, and is, most of the time, pretty safe. What he was saying, really, was that New York had become the Web. Or perhaps more, even: that New York was the Web before the Web was the Web, characterized by the same free-flowing interaction, 24/7 rhythms, subgroups, and demimondes.

(via Mind Hacks) ¶ 0

2006/12/8

An interesting article, by danah boyd, on the social dynamics of Friend relations in social software, predominantly Friendster and MySpace:

The most common reasons for Friendship that I heard from users [11] were:Boyd, er, boyd describes some ways in which the design of a social-network implementation (i.e., is Friendship transitive, what information is displayed about users, how access to information is controlled, and whether or not friendships can be ranked) influences the social dynamics:

- Actual friends

- Acquaintances, family members, colleagues

- It would be socially inappropriate to say no because you know them

- Having lots of Friends makes you look popular

- It's a way of indicating that you are a fan (of that person, band, product, etc.)

- Your list of Friends reveals who you are

- Their Profile is cool so being Friends makes you look cool

- Collecting Friends lets you see more people (Friendster)

- It's the only way to see a private Profile (MySpace)

- Being Friends lets you see someone's bulletins and their Friends-only blog posts (MySpace)

- You want them to see your bulletins, private Profile, private blog (MySpace)

- You can use your Friends list to find someone later

- It's easier to say yes than no

Collecting is advantageous for bands and companies and thus, they want to make it advantageous for participants to be fans; because there is little cost to do so, those who connect figure, "why not?" When Friends appear on someone's Profile, there is a great incentive to make sure that the Profiles listed help say something about the individual.

When a Friend request is sent, the recipient is given two options: accept or decline. This is usually listed under a list of pending connections that do not disappear until one of the two choices is selected. While most systems do not notify the sender of a recipient's decline, the sender can infer a negative response if the request does not result in their pages being linked. Additionally, many systems let the sender see which of their requests is still pending. Thus, they know whether or not the recipient acted upon it. This feature encourages recipients to leave an awkward relationship as pending but to complicate matters, most systems also display when a person last logged in on their Profile. Since it is generally known that the pending list is the first thing you see when you login, it is considered rude to login and not respond to a request. For all of these reasons, it's much easier to just say yes than to face questions about why the sender was ignored or declined.There is more fodder here for those who hold that MySpace is evil; the site, it seems, is designed to clutter social networks with "junk friends" (i.e., strangers and brand campaigns) and deliberately amplify social drama. Case in point: its "Top 8" feature, which allows users to say who is and isn't their bestest friend ever, and/or to whine about not being in someone's Top 8.

"As a kid, you used your birthday party guest list as leverage on the playground. 'If you let me play I'll invite you to my birthday party.' Then, as you grew up and got your own phone, it was all about someone being on your speed dial. Well today it's the MySpace Top 8. It's the new dangling carrot for gaining superficial acceptance. Taking someone off your Top 8 is your new passive aggressive power play when someone pisses you off."

When Emily removed Andy from her Top 8, he responded with a Comment [13] on her page, "im sad u took me off your Top 8." Likewise, even though Nigel was never on Ann's Top 8, he posted a Comment asking, "y cant i b on ur top 8?" These Comments are visible to anyone looking at Emily or Ann's page. By taking their hurt to the Comment section rather than privately messaging Ann and Emily, Nigel and Andy are letting a wider audience know that they feel "dissed."

"Myspace always seems to cause way too much drama and i am so dang sick of it. im sick of the pain and the hurt and tears and the jealousy and the heartache and the truth and the lies ... it just SUCKS! ... im just so sick of the drama and i just cant take it anymore compared to all the love its supposed to make us feel. i get off just feeling worse. i have people complain to me that they are not my number one on my top 8. come on now. grow up. its freaking myspace." -- OliviaSmall design decisions make a profound difference to how a social web site works. MySpace seems to be designed to maximise social pressures and exacerbate social anxiety and drama. This may be out of thoughtlessness (which wouldn't surprise me, given the generally inelegant design of the site), as part of some kind of Milgram/Zimbardo-esque psychological experiment (see also: Reality TV), or just an externality of maximising appeal to advertisers and youth marketers. LiveJournal, in contrast, goes out of its way to minimise drama; for example, its notification engine won't tell you if you've been unfriended.

(via Boing Boing) ¶ 0

2005/6/22

According to a study at Flinders University, good social networks of close friends are more beneficial to a long life than family members:

The new study followed almost 1500 Australians, initially aged over 70. Those who at the start reported regular close personal or phone contact with five or more friends were 22% less likely to die in the next decade than those who had reported fewer, more-distant friends. But the presence or absence of close ties with children or other relatives had no impact on survival.Which all flies in the face of conventional wisdom, that supportive, tightly-knit families are the key to health and happiness. Though the explanation for this could be that it is not so much a truth as a manifestation of an evolved cultural response to the environment, a mantra of family-values repeatedly recited to counterbalance the ambient irritation of interaction with family members and reinforce stable social structures.

2005/6/8

An unexpected dividend from the Enron scandal: the corpus of emails turned over to investigators by the dodgy energy-trading company (which, in this case, includes everything ever emailed through enron.com) fell into the hands of academics and has since proven to be a boon to social network researchers.

Some of the methods in the paper (i.e., automatic community detection) look useful; it'd be interesting to apply them to, say, LiveJournal, Flickr or even inter-blog links.

(via bOING BOING) ¶ 0

2003/8/14

Someone has written a program for spidering Friendster and rendering a graph of the social network (downloadable, Windows-only).

Sounds interesting in theory, though in practice it depends on how many people have signed up. When I played around with Friendster, my network was very sparse, with few people being bothered to sign up and hassle their friends into doing so. It wasn't that nobody would be my friend. I had plenty of those; just that very few of them bothered to actually add any other friends (or fill in more than the bare minimum of details about themselves). Mind you, the fact that Friendster is all but useless except for finding sexual partners sort of limits its audience; perhaps in Australia, using computers for getting laid is still seen as the last refuge of sad losers, rather than the playground of cutting-edge cyber-nerverts.

tribe.net would be somewhat more interesting to graph, as it's a multi-use system (useful for posting announcements, selling stuff, shooting the bull about your favourite TV show/band/sports team and meeting people), thus giving denser social networks. LiveJournal would probably yield even more densely interconnected networks; also, since LJ has an open API, it shouldn't be too hard to rig up something to spider it and plot a graph, possibly even correlated with a physical map of the real world. I wonder whether anyone has thought of this already.

2003/3/18

A (somewhat cursory) look inside the neo-Bokononian world of social network analysis, which uses computers to analyse patterns of interaction between people or their preferences and map the informal, emergent social structures (or karasses as Bokonon called them) in organisations or societies. This has applications from art to hunting terrorists (or anyone else of interest; apparently this area is known technically as conspiracy detection) to detecting breakdowns in communication within a larger society:

The karass is that group of friends from college who have helped one another's careers in a hundred subtle ways over the years; the granfalloon is the marketing department at your firm, where everyone has a meticulously defined place on the org chart but nothing ever gets done. When you find yourself in a karass, it's an intuitive, unplanned experience. Getting into a granfalloon, on the other hand, usually involves showing two forms of ID.

Krebs used InFlow to analyze the network of book purchases surrounding two best-selling titles, one from the left (Michael Moore's Stupid White Men) and one from the right (Ann Coulter's Slander). "What I got were two cliques that were about as distinct as they could be. I kept looking for paths that crossed between them. Every time I tried to follow one of these paths, I'd go out three or four steps, and then boom, I'm right back in the clique." Most strikingly, the two networks intersected only on a single title: Bernard Lewis's What Went Wrong. Otherwise, the two groups were engrossed in entirely different reading lists, with no common ground.

(via FmH)